Table of Contents

Introduction

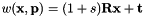

The appearance-based approaches, also known as template-based approaches, are different in the way that there is no low-level tracking or matching processes. It is also possible to consider that this 2D model is a reference image (or a template). In that case, the goal is to estimate the motion (or warp) between the current image and a reference template.

In ViSP such an algorithm is proposed. It allows to track a template using image registration algorithms. Contrary to the common approaches based on visual features, this method allows to be much more robust to scene variations.

The video below shows the result of the template tracking applied on a painting.

Source code

The following source code also available in template-matching-visp.cpp allows to estimate the homography between the current image and the reference template defined by the user in the first image of the video. The reference template is here defined from a set of triangles. These triangles should rely on the same plane to estimate a consistant homography.

Source code explained

Hereafter is the description of the most important lines in this example. The template tracking is performed using vpTemplateTrackerSSDForwardAdditional class implemented in ViSP. Let us denote that "SSDForwardAdditional" refers to the similarity function used for the image registration. In ViSP, we have implemented two different similarity functions: the "Sum of Square Differences" (vpTemplateTrackerSSD classes [1]) and the "Zero-mean Normalized Cross Correlation" (vpTemplateTrackerZNCC classes [5]). Both methods can be used in different ways: Inverse Compositional, Forward Compositional, Forward Additional, or ESM.

Here we include the header of the vpTemplateTrackerSSDForwardAdditional class that allows to track the template. Actually, the tracker estimates the displacement of the template in the current image according to its initial pose. The computed displacement can be represented by multiple transformations, also called warps (vpTemplateTrackerWarp classes). In this example, we include the header vpTemplateTrackerWarpHomography class to define the possible transformation of the template as an homography.

Once the tracker is created with the desired warp function, parameters can be tuned to be more consistent with the expected behavior. Depending on these parameters the perfomances of the tracker in terms of processing time and estimation could be affected. Since here we deal with 640 by 480 pixel wide images, the images are significantly subsampled in order to reduce the time of the image processing to be compatible with real-time.

The last step of the initialization is to select the template that will be tracked during the sequence.

The vpTemplateTracker classes proposed in ViSP offer you the possibility to defined your template as multiple planar triangles. When calling the previous line, you will have to specify the triangles that define the template.

Let us denote that those triangles don't have to be spatially tied up. However, if you want to track a simple image as in this example, you should initialize the template as on the figure above. Left clicks on point number zero, one and two create the green triangle. Left clicks on point three and four and then right click on point number five create the red triangle and ends the initialization. If ViSP is build with OpenCV, we also provide an initialization with automatic triangulation using Delaunay. To use it, you just have to call vpTemplateTracker::initClick(I, true). Then by left clicking on points number zero, one, two, four and right clicking on point number five initializes the tracker as on the image above.

Next, in the infinite while loop, after displaying the next image, we track the object on a new image I.

If you need to get the parameters of the current transformation of the template, it can be done by calling:

For further information about the warping parameters, see the following Warping classes section.

Then according to the computed transformation obtained from the last call to track() function, next line is used to display the template using red lines.

Warping classes

In the example presented above, we focused on the vpTemplateTrackerWarpHomography warping class which is the most generic transformation available in ViSP for the template trackers. However, if you know that the template you want to track is constrained, other warps might be more suitable.

vpTemplateTrackerWarpTranslation

with the following estimated parameters

with the following estimated parameters

This class is the most simple transformation available for the template trackers. It only considers translation on two-axis (x-axis and y-axis).

vpTemplateTrackerWarpSRT

with

with

The SRT warp considers a scale factor, a rotation on z-axis and a 2D translation as in vpTemplateTrackerWarpTranslation.

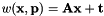

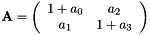

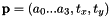

vpTemplateTrackerWarpAffine

with

with  ,

,  and the estimated parameters

and the estimated parameters

The template transformation can also be defined as an affine transformation. This warping function preserves points, straight lines, and planes.

vpTemplateTrackerWarpHomography

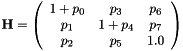

with

with  and the estimated parameters

and the estimated parameters

As remind, the vpTemplateTrackerWarpHomography estimates the eight parameters of the homography matrix  .

.

vpTemplateTrackerWarpHomographySL3

with

with

The vpTemplateTrackerWarpHomographySL3 warp works exactly the same as the vpTemplateTrackerWarpHomography warp. The only difference is that here, the parameters of the homography are estimated in the SL3 reference frame.

How to tune the tracker

When you want to obtain a perfect pose estimation, it is often time-consuming. However, by tuning the tracker, you can find a good compromise between speed and efficiency. Basically, what will make the difference is the size of the reference template. The more pixels it contains, the more time-consuming it will be. Fortunately, the solutions to avoid this problem are multiple. First of all lets come back on the vpTemplateTracker::setSampling() function.

In the example above, we decided to consider only one pixel from 16 (4 by 4) to create the reference template. Obviously, by increasing those values it will consider much less pixels, which unfortunately decrease the efficiency, but the tracking phase will be much faster.

The tracking phase relies on an iterative algorithm minimizing a cost function. What does it mean? It means this algorithm has, at some point, to stop! Once again, you have the possibility to reduce the number of iterations of the algorithm by taking the risk to fall in a local minimum.

If this is still not enough for you, let's remember that all of our trackers can be used in a pyramidal way. By reducing the number of levels considered by the algorithm, you will consider, once again, much less pixels and be faster.

Note here that when vpTemplateTracker::setPyramidal() function is not used, the pyramidal approach to speed up the algorithm is not used.

Let us denote that if you're using vpTemplateTrackerSSDInverseCompositional or vpTemplateTrackerZNCCInverseCompositional, you also have another interesting option to speed up your tracking phase.

This function will force the tracker to only consider, in the reference template, the pixels that have an high gradient value. This is another solution to limit the number of considered pixels.

As well as vpTemplateTrackerSSDInverseCompositional::setUseTemplateSelect() or vpTemplateTrackerZNCCInverseCompositional::setUseTemplateSelect(), another function, only available in vpTemplateTrackerSSDInverseCompositional and vpTemplateTrackerZNCCInverseCompositional is:

By increasing this root mean square threshold value, the algorithm will reduce its number of iterations which should also speed up the tracking phase. This function should be used wisely with the vpTemplateTracker::setIterationMax() function.

How to get the points of the template

The previous code provided in tutorial-template-tracker-visp.cpp can be modified to get the coordinates of the corners of the triangles that define the zone to track. To this end, as shown in the next lines, before the while loop we first define a reference zone and the corresponding warped zone. Then in the loop, we update the warped zone using the parameters of the warping model that is estimated by the tracker. From the warped zone, we extract all the triangles, and then for each triangles, we get the corners coordinates.

With the last line, we also sho how to get and display an orange rectangle that corresponds to the bounding box of all the triangles that define the zone.

The resulting drawings introduced previously are shown in the next image. Here we initialize the tracker with 2 triangles that are not connex.

1.8.14

1.8.14